Stepped-up demand from the poultry industry has led to higher soymeal consumption in India, a trend that is expected to continue over the next several years, according to a new report from Rabobank entitled, “Outlook of India’s Soymeal Industry.”

Rohit Dhanda, a grain and oilseeds analyst at Rabobank, noted in the Sept. 25 report that soymeal consumption in India increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19% between 2007 and 2017, rising to 5.4 million tonnes in 2017 from 800,000 tonnes in 2007.

Moving forward, Rabobank expects soymeal demand in India to grow at a CAGR of 7%, which would lead to consumption surpassing 9.5 million tonnes by 2025.

“The growth of the poultry industry has resulted in a proportionate rise in domestic soymeal consumption — soymeal is the major source of feed protein for poultry,” Dhanda noted in the report.

He said feed demand in India represents over 90% of total soymeal consumption, while food usage ranges between 8% and 10%.

As India’s domestic soymeal demand continues to grow, Dhanda said the country’s supplies have been subject to fluctuation. He said soybean farmers will need better seed technology and agronomic practices to stabilize domestic production.

“Apart from the possibility of blending soymeal with other oilseed meals, the fortification of compound poultry feed with amino acids to replace soymeal as a protein source is also an option — but so far, this is an undeveloped market in India,” he said. “Therefore, Rabobank expects India’s poultry industry to remain largely dependent on soymeal as a protein source in the near future. Rising domestic demand of soymeal could help the domestic soybean price sustain levels that are attractive to farmers, which is expected to result in sustained acreage for Indian soybean farmers in the future. However, the large presence of marginal farmers and fragmented land will remain a hindrance in strategic investments at the farm level.”

With demand on the rise, India may need to turn to more imports to meet its soymeal needs. However, one of the challenges that India faces is its reluctance to import genetically modified soybeans. According to Rabobank, only 12% of global soybeans are non-GM in nature (including India’s own production), and their production is scattered across the globe, including Argentina, China, Russia and Africa.

“Depending on supplies in individual years, importing such big volumes of non-GM soybeans or soymeal could also be prohibitively expensive for India, due to the attached price premium compared to GM soybeans,” Dhanda said.

He added, “The government’s future policy decisions to systematically increase domestic soy production, or allow soybean or soymeal imports, will be critical.”

India is the fifth largest producer of soybeans globally, after the United States, Brazil, Argentina, and China. In the past, it has been an important supplier of soymeal to Southeast Asia, the E.U., and the Middle East. But Dhanda said in recent years, India has been losing export market share to South American soybean meal exporters due to increasing domestic demand from the growing poultry industry, along with soybean production constraints in 2014, 2015, and 2017 — a result of adverse weather.

Dhanda said Rabobank expects India to become a net importer of soybeans, only exporting limited amounts of soymeal (ie non-GM serving E.U. niche markets) in the future if domestic production does not rebound.

Rise protein consumption

Economic growth and increasing disposable incomes have resulted in a rise of animal protein in diets, said Dhanda. While fish and seafood are the most-consumed animal proteins, poultry and eggs are considered affordable and socially acceptable — and fast-rising demand has resulted in strong growth in India’s poultry industry.

India’s net consumption of poultry grew at 7% CAGR, from 2.2 million tonnes in 2007 to 4.4 million tonnes in 2017, he said. The growth of the poultry industry has resulted in a proportionate rise in domestic soymeal consumption.

He noted that while the country is a major rapeseed and cottonseed producer, high fiber content and the presence of erucic acid and glucosinolates in cottonseed and rapeseed meal limit their usage by the poultry industry.

Soybean acreage is increasing in India, but a lack of disruptive seed technology and inefficient farming practices mean that the country’s soybean output fluctuates a lot and remains largely dependent on monsoon performance, Dhanda said.

“Uneven rainfall distribution on major soy regions impacts the yields significantly, while the issue is further exaggerated by a poor seed-replacement ratio at the farm level,” Dhanda said.

Exports declining

After a 12-year period in which India’s soybean production increased at a 6% CAGR, output reached a high of 10.7 million tonnes in 2012. Rabobank noted that despite seeing a growth trend in net planted acres, India’s domestic production declined to 8.7 million tonnes in 2017, due to low yields.

Consequently, with domestic soymeal consumption on the rise, soymeal exports from India are expected to shrink further. Rabobank said India’s soymeal exports to Southeast Asia, the traditional importing region, declined to 500,000 tonnes in 2017, from a historic high of 3.2 million tonnes in 2008.

This trend is to the detriment of France and Germany, which have emerged as important importers for Indian soymeal, a situation that is expected to continue because of the core demand for non-GM soymeal volumes in the E.U. Rabobank said it expects future soymeal exports from India to vary between 500,000 tonnes and 1 million tonnes, depending upon surplus soymeal availability in the domestic market.

What the future holds

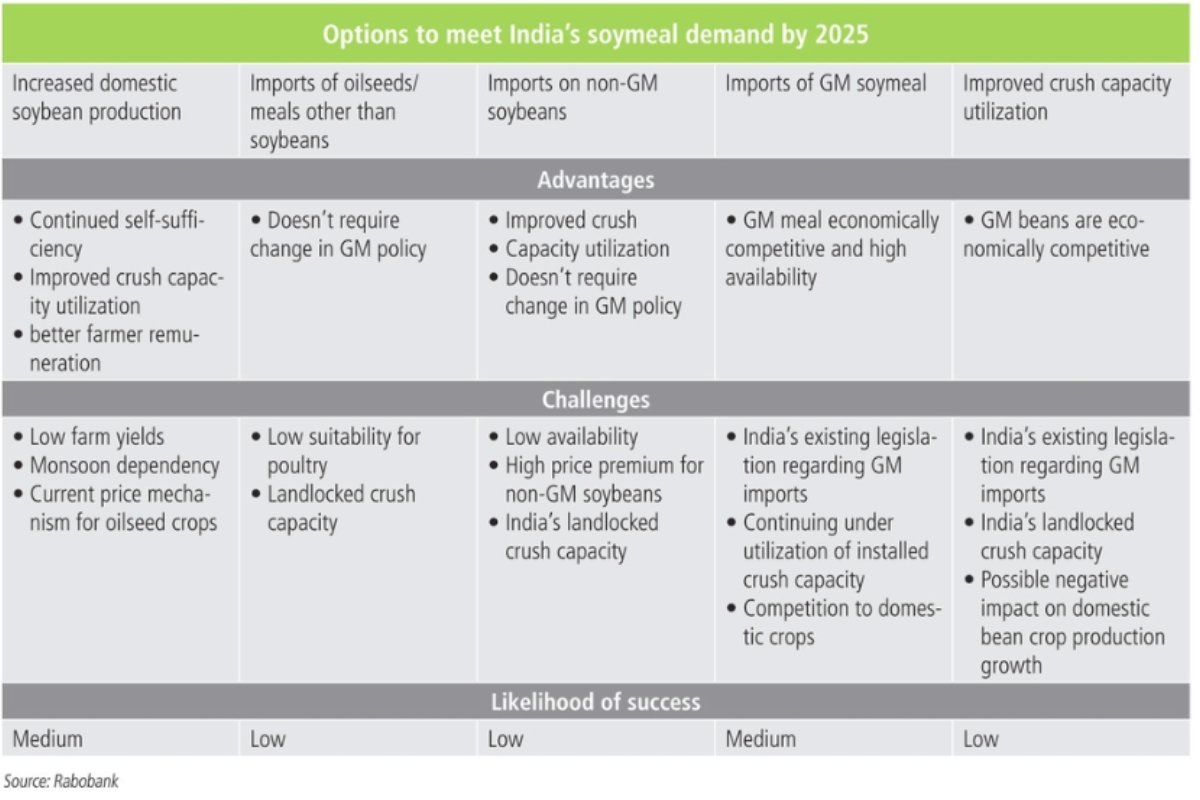

In summarizing the situation, Rabobank believes that India will have to develop a protein feed strategy for the future.

“India’s soymeal import demand by 2025 is expected to be 1.5 million tonnes in an average production year — but in the extreme case of a really bad domestic soybean crop, this could be up to 5 milllion tonnes,” Dhanda wrote. “The government will have to focus on increasing domestic soybean production in order to meet rising soymeal demand if imports are to be prevented. If domestic production remains unable to meet demand, India would need to open its market to imports of soymeal from the global market.”

He said India may not allow imports of GM soybeans because of the bureaucratic complexity involved, although non-GM soybean import volumes could increase in the future.

“However only 12% of global soybeans are non-GM in nature, including India’s own domestic production, and their production is scattered across various geographies, including Argentina, China, Russia and Africa,” he said. “Depending on supplies in individual years, imports of such big volumes of non-GM soybeans or soymeal could also be prohibitively expensive for India, due to the attached price premium compared to GM soybeans.”

Dhanda finished his report by outlining three possible scenarios that could occur by 2025:

Optimum production case: India could meet its soymeal demand on its own if soybean production surpasses 13 million tonnes annually. For this, improving farm yields must be the main focus. Dhanda said the probability of this scenario taking place is “low.”

Average production case: India would either require imports in the form of soybeans or soybean meal.

Worst production case: With below-average acreage and poor yields due to a bad monsoon, India’s import demand for soymeal or soybeans in soymeal equivalent could be as high as 5 million tonnes.

Dhanda described the combined probability of the last two scenarios as “high.”

Dhanda noted that higher soymeal prices also impact the profitability of the domestic poultry industry, “so unless domestic poultry meat prices move up in tandem with soymeal prices, it will become difficult for India’s poultry industry to sustain business growth in years of squeezed margins as a result of high meal prices.”

“The government’s future policy decisions to systematically increase domestic soybean production, or allow soybean or soymeal imports, will be critical,” he said.